So, you need to collect data.

You may have seen this coming or you may have been voluntold to do this. In either case, it’s worth confirming what actually needs to be collected. In other words, separate the nice-to-have or interest-related data you want from the crucial data you need in order to make decisions.

As you begin this journey, know that you are not on your own. I’m not just talking about myself or this blog but rather about all the resources you have available for guidance.

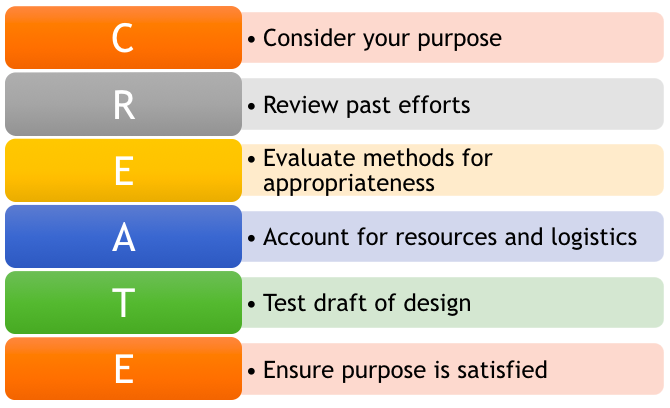

I regularly fall back on this “CREATE” acrostic I made for method selection. And at least the first few points are a fitting place to start for crafting assessment questions, too.

The first point, consider your purpose, is a reminder to consider the mission, goals, and outcomes of your area in order to connect them with the data you plan to collect.

As a psychometric good practice, you should first identify what you are measuring before you determine the best way to measure it. So look to your area’s foundational documents or purpose to orient yourself before getting started.

Reviewing past efforts is an important step in crafting questions, too. Of the past data collected or instruments/methods used, were the results used? If not, the instrument must not have been collecting needed data. Perhaps it was intended to, so you could look there for inspiration in crafting your own questions.

However, an existing instrument won’t necessarily be appropriate for your needs nor will it absolutely be the best method to capture your data. If you’re collecting data for the first time, don’t despair! Remember the purpose of your assessment and begin thinking about what you need to measure.

Outline Your Topics

Before worrying about the exact language or structure of each question, make sure you figure out an outline or the set of topics your questions should cover. Start brainstorming responses to these three questions:

- Why am I collecting data?

- Who am I collecting data from or about?

- What do I need to know?

Start by writing down the question(s) you need to answer or report on with your results. This could come from the initial charge of the data collection or from your team’s perspective as you think more about the intervention and intended population.

Be sure to also keep in mind the scope of your area and what you can control. This is key, as people often start rattling off everything that could be important to capture as data. While this can be great in the brainstorming process, you need to eliminate questions that provide data you cannot possibly use.

For example, if you are most concerned about what student learning outcomes were gained from a campus-wide speaking event, you probably shouldn’t ask about the convenience of the venue — especially if there is only one space where such an event could be held. This question strays from what you can control and won’t provide you with any data about student learning.

Determine the Structure

Think about how you’ll structure your questions. Reflecting on purpose and what you need to know helps here, as different structures will yield different data.

For example, if you’re concerned with how useful a resource might be, consider these structures and results:

- Open-ended: The question might be “How useful was X?”. This allows respondents to explain — in their own words — whether something was useful. While that’s great, recognize that you’ll have to review such responses individually, then code them for themes in order to understand the results.

- Closed-ended (set answers, scaled) The question might be, “How useful was X? (Very useful – Not at all useful)”. This structure makes reporting easy because you can simply calculate the frequency of each response. However, there may not be consistency in respondent standards of usefulness. In other words, the event may have been useful (or not) in different ways for different students. Since it’s a closed-ended question, there’s no room for elaboration or rationale.

Either of the above questions could answer a reporting question of “How useful did students find X?”. The open-ended responses would require a lot more time to understand, but the responses will hopefully yield rich detail about the topic.

On the other hand, closed-ended responses could quickly be shared as “X% of students found it useful or very useful.” Yet, there would be no additional information as to why students felt that way.

There’s no definitively right or wrong approach here, but the process to get to the results (and the results themselves) can look extremely different.

Considerations for question structure go beyond the aforementioned example. You could, for example, look at yes/no vs. scales for questions. When presenting options, you could have check-all-that-apply vs. limited selection questions.

Again, one of these question methods is not objectively better than the other, but one may be better suited to your purpose and needs.

Edit and Refine

Once you know your topics and question structures, you can start writing and refining the wording of your questions. Articulate your questions and share them with others (including staff, faculty, students) to review in light of several considerations:

- Are you using familiar and clear language? Think about your audience. Avoid jargon and provide definitions and context as needed. Also, be sure that what others perceive that you’re asking is the same as your intent.

- Are you just asking one thing? It can be easy to accidentally fuse two questions into one. I did it in the previous question. These are different questions, which may present a dilemma for someone to give a single response. Keep questions limited to one item or topic at a time. Otherwise, you may get skewed results.

- Is your language leading or biased? Be careful not to include questions that make assumptions about the respondent nor prompt respondents to answer in a certain way. In asking about usefulness, include clear language or context for understanding but not to solicit a certain response.“How useful was the resource in completing your assignment?” is more objective than “Having intentionally selected the materials to aid in your success, how useful was the resource in completing your assignment?”.

- Are you asking collecting unique data? Unique has two meanings here. First, don’t collect data you already have. Second, make sure your question is distinct and separate from every other question. Be mindful of overlap.

Reflect, Pilot and Revise

At this point, you’ve crafted good questions.

In doing so, however, you may have crafted content beyond the purpose and scope of your data collection. As such, revisit the purpose and make sure that all of your questions serve a purpose and still meet your needs.

Write notes on purpose or use-case next to each question to make sure you’re not asking any unnecessary questions. Also, consider the flow and order of questions you are asking.

Here are some tips related to the ordering of your questions:

- Group questions together according to topic, subject, or scale.

- Ask questions in order of respondent experience (for example: pre-orientation communication, followed by orientation check-in, morning events, and afternoon events).

- Start with easy or low-stakes and work your way up to more personal questions,

- Ask important questions early in case people decide to stop providing data at a certain point.

Once you are confident that your questions fit your intended purpose, share your questions with others for feedback. Ideally, you can share your questions with some of your intended audience. As they give feedback, revise and update your questions accordingly.

A Note for Application

Although I presented this information in a linear fashion, know that the process may not always play out that way for you.

For example, piloting can be an ongoing process as you craft content. Or while refining questions, you might realize that your original purpose or scope for asking questions was too limited (or too broad). All of that is fine and normal. While it may seem like you are not making progress, you are!

The effort and intentionality you apply now will pay off in helping you gather useful data later. It will also help prepare your analysis and reporting process by knowing what kind of data you can anticipate.

I hope this information proves useful to you; it’s served me well over the years.

Do you have any additional tips on crafting assessment questions? This isn’t an exhaustive list, so we’d love to learn of more. Tweet us at @themoderncampus and @JoeBooksLevy.