Discussing power dynamics, especially in the context of privilege and oppression, is not an easy conversation to have with students.

You could earn a Ph.D. while studying the concept of power and still learn new ways in which it interacts with every relationship and social construct.

But as complex and uncomfortable as the topic of power may be, students need to understand how it plays a role in their organizations and communities.

This post will provide you with resources and activities to help you teach students about power dynamics. Additionally, I encourage you to consult with your office of diversity programs or multicultural affairs, social work or sociology faculty, or trained social justice facilitators when putting together your curriculum or dialogue.

Done carelessly, discussing students’ experiences with power, privilege, and oppression can cause students with marginalized identities to be retraumatized and students with privileged identities to disengage. If you feel that you are not up to the task alone, consider hiring someone or collaborating with a coworker who is skilled in managing dialogues across differences.

I suggest checking out or brushing up on the following resources so that you can help students get the most out of your program or dialogue:

- Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) Model

- Helping Students Explore Their Privileged Identities

- “Are You Ready To Talk?” Toolkit

- Start Talking: A Handbook for Engaging Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education

- From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces

- Social Justice 101 Resources

- Social Justice Toolkit

Take your time reviewing these resources and doing the self-reflection that is required to unpack your own power and privileges. The more prepared you are, the better experience your students will have.

Now, take a breath and let’s begin.

Definitions

When discussing organizational structures and power dynamics with students, it will be important to agree upon shared definitions for the terms below. Framing the dialogue around shared definitions will pave the way for deeper reflections on how power dynamics impact every interaction within an organization.

Power

Power can be difficult to discuss with students because it is such an abstract concept. Let’s start with a definition by the social justice facilitator Leigh Tompson, who says that power is:

“The ability to influence and/or act”

If you were to ask students “who has power?” within an organization, they will most likely identify people in formal positions of authority. But that answer isn’t entirely correct. It’s actually a bit of a trick question because everybody within an organization has some power — just different amounts of it depending on the situation.

Teaching students to recognize and leverage different types of power can help them to build more equitable and inclusive organizations.

In this video created for CrashCourse, Evelyn Ngugi identifies five forms of personal power.

- Coercive power: Having control over some kind of punishment. An example of this is if a student with crucial skills threatens to leave a student organization in the middle of an important project because they don’t like how they’re being treated. The student has power because they have something that the organization needs and can punish the organization by withholding their skills.

- Reward power: Having control over things that others want. If the student organization president chooses which general members will attend a conference based on how often members volunteer for the organization, then the president has reward power.

- Legitimate power: Having authority based on holding a position within the organization. Building trust and acting equitably is key to having people respect this type of power. Students will easily recognize executive board members and administrators who have this type of power.

- Charismatic power: People are most motivated to do things for someone whom they like and respect, especially if the followers believe in the leader’s vision. Student activists often use charismatic power to get others to join their cause.

- Expert power: People trust the advice of someone who is knowledgeable about a complicated topic. Students may perceive professors with advanced degrees as having expert power. First-year students might identify upperclass students as having power because these more experienced students better understand how the institution works.

After you review these types of personal power with students, pose these discussion questions — from Opportunity Collaboration — to help students explore their experiences with power:

- When was the last time you felt powerless?

- When was the last time you felt powerful?

- What do you love about having power?

- When was the last time you gave away your power (deliberately or otherwise)?

- When was the last time you usurped someone else’s power?

- In what situations do you not trust yourself with too much power?

George Aye, the Director of Innovation at the Greater Good Studio, describes his reaction when he first answered these questions:

“These questions (and others like them) had me reeling, and my answers felt raw, clumsy, and crude. It made me realize how little practice I had in thinking or even talking about power. Since then, I’ve come to better understand that power is so many things at the same time: an emotion, a currency, a source of pride, a place of strength, a sign of vulnerability, an advantage to play, a lever to pull, a tool to wield with precision or without care. And it’s been present in every relationship I’ve ever had and will be present in every interaction yet to come.”

Privilege & Oppression

Once students can identify the ways in which power plays out in their personal relationships, the next step is to understand how privilege affects who has power. From there, students grow in their understanding of how the power of many individuals can contribute to or dismantle systems of oppression.

Privilege is defined by Leigh Tompson as:

“Unearned benefits given to members of one social group as a result of the systematic targeting or marginalization of another social group”

There are many team-builder activities and leadership exercises you can facilitate to help students understand social identity and privilege. I especially like the social identity wheel and the privilege for sale activity. The Social Justice Toolbox, Diversity Toolkit, and Diversity Activities Resource Guide offer great tools too.

You may also have heard of (or done) a “privilege walk”, but bear in mind that some social justice facilitators no longer recommend this activity. You can learn more here and here.

Being able to articulate why people who hold privileged identities have more power will lead students to a clearer understanding of oppression.

Leigh Tompson defines oppression as:

“The systematic targeting or marginalization of one social group by another social group for the benefit of the more powerful social group”

Students should grasp that oppression is systemic and reinforced on personal, institutional, and cultural levels. Fortunately, students can work to dismantle systems of oppression. They can start by using their power to push for equity and inclusion within their spheres of influence, including their student organizations, their workplaces or volunteer spaces, and other communities they belong to.

White Supremacy Culture

Culture plays an important role in how any organization functions.

Dismantling Racism offers this concise definition:

“A culture is a way of life of a group of people – the behaviors, beliefs, values, and symbols that they accept, generally without thinking about them, and that are passed along by communication and imitation from one generation to the next”

Culture is powerful precisely because it is often invisible even to people within that culture. So, for students to increase equity and inclusion within their spheres of influence, they must understand what a culture of white supremacy entails and how they have been socialized into it.

Dismantling Racism gives the following definition of white supremacy culture:

“The idea (ideology) that white people and the ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions of white people are superior to People of Color and their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions.”

Tema Okun described the 15 characteristics of white supremacy culture that show up in organizations, regardless of the racial makeup of the organization’s members. Using these descriptions and antidotes, you could ask students to share how they’ve observed these characteristics in their own communities.

As you discuss white supremacy culture, the following resources can provide scaffolding for students as they explore how to dismantle white supremacy culture and replace it with a culture that shares power more equitably:

- Introduction to Critical Race Theory

- “Seeing White” podcast

- White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

- White Supremacy Culture & Remote Work

- Decentering Whiteness

Activities & frameworks

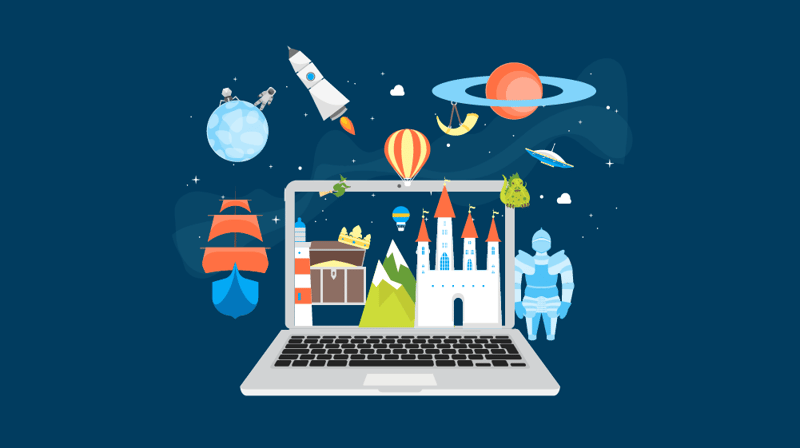

It may be hard for students to imagine communities that are based on a culture of power-sharing — not because they don’t want to be equity-oriented leaders, but because they may not have ever experienced this type of culture before.

To counter this, you can teach students about the equityXdesign process and Liberating Structures activities. If you have the opportunity, have students experience an unconference to see power-sharing principles in action. (I’ll tell you all about these three resources a bit below.)

Designing For Equity

Because organizational structures that maintain power imbalances are products of design, they can be redesigned.

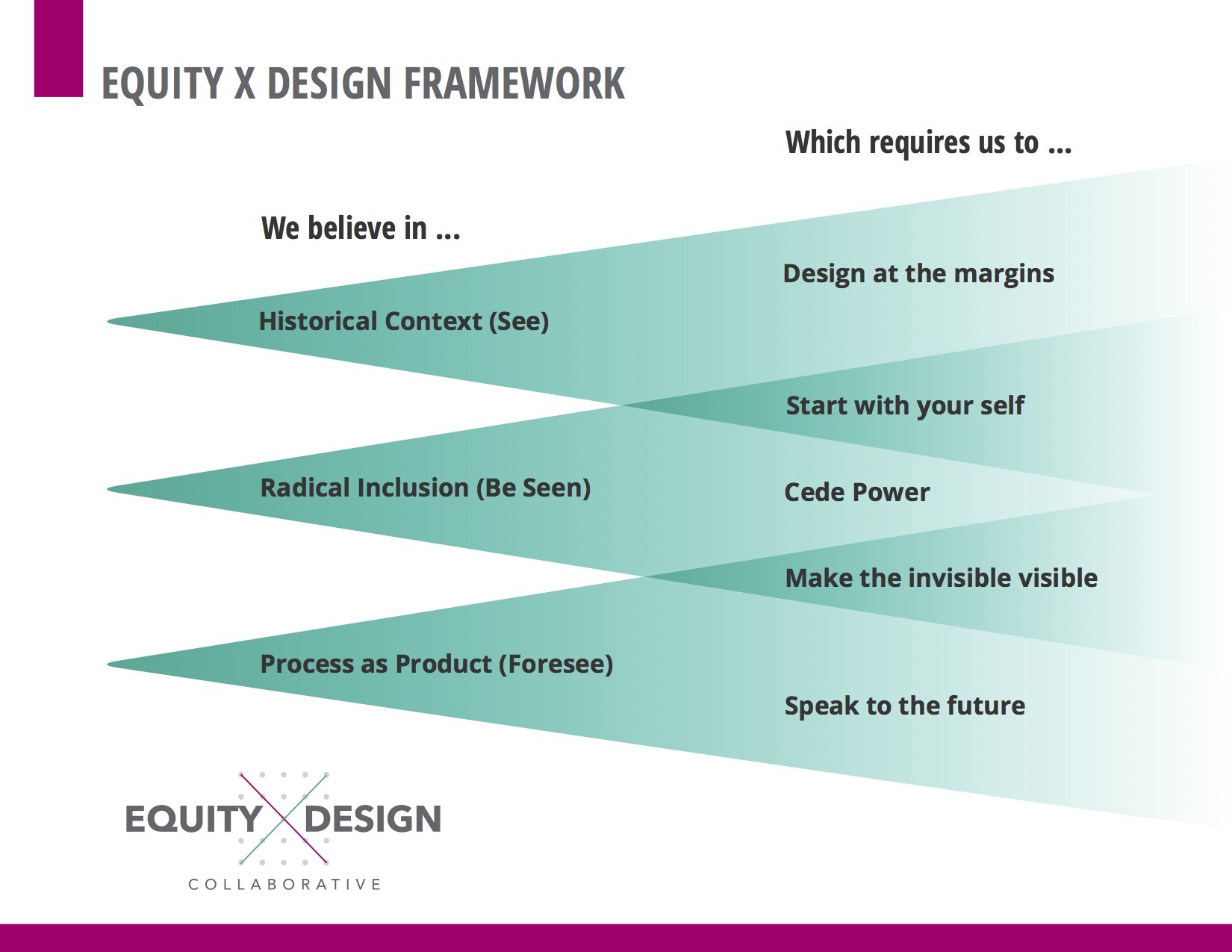

The equityXdesign process was developed by 288 Accelerator, The Equity Lab, and Equity Meets Design. This process builds off of the design thinking methodology to provide a framework for identifying and solving equity issues. The equityXdesign process can help students understand where power is concentrated and how to “do” equity.

There are three core beliefs guiding this process:

- Historical context matters (see): In order to understand how current processes, policies, and conditions came to be as they are, we must investigate the history surrounding the thing we are designing, the place we are designing in, and the community we are designing with.

- Radical inclusion (be seen): Not only must diverse stakeholders be brought to the decision table, but we must also be intentional about building community. This means actively eliminating barriers to participation and creating spaces wherein everyone can be their authentic selves.

- Process as product (foresee): We must always be mindful that to design for equity, we must design in an inclusive way. Inclusive design practices raise the voices of the marginalized and build relationships across differences.

You can understand how these core beliefs are intertwined with equityXdesign’s five design principles by viewing the graphic below. For a more comprehensive explanation of the concepts, read the official report or this handout.

Christine Ortiz from Equity Meets Design has compiled a list of resources and written a book detailing tools that can be used in the equityXdesign process. The diagrams of the process and corresponding worksheets show how equityXdesign can be applied to programs, products, services, processes, and so much more.

For example, a student government might use this framework to make their process for setting funding priorities more equitable. After going through the process, they may decide to increase funding for underrepresented identity-based organizations or to provide seed funding for a campus food bank.

Student admissions ambassadors could work with their supervisors to improve the campus tour by identifying ways to improve visitors’ experiences. The equityXdesign process could help them identify when visitors may need breaks (to physically rest or process information) or lead the staff to discover that they should hire more multilingual ambassadors.

Unconferences

An unconference is an event with its agenda set by attendees. So, there are no keynote speakers, no session proposals, and no designated networking times. As I’ll explain soon, anyone can facilitate a session, regardless of whether or not they are recognized as an “expert” on a topic.

Hosting or sponsoring attendance at an unconference is a great way to demonstrate to students how to subvert expectations for traditional power roles.

Here’s what makes an unconference different from conferences your students may be used to:

- The agenda is set using a methodology known as Open Space Technology. Participants collaboratively create it by writing a topic or discussion question related to the conference theme in a time slot, such as in the schedule pictured below.

- Sessions focus on learning from community-wisdom, not a sage-on-the-stage. Presentations and panels are replaced with formats such as fishbowl discussions and problem-solving activities. The participant who proposed the session topic does not have to facilitate the session; the group organically decides what to do once they gather together.

- The Law of Two Feet states that if a participant becomes uninterested in a session at any time, they are encouraged to leave and join another session. It’s not considered rude; if they are not learning something useful, then why stay?

The unconference schedule board at Planning Camp

At an unconference, anyone can propose a topic, facilitate a session, and use the Law of Two Feet to choose how they want to engage. Traditional expectations of power dynamics are rejected in favor of building community though this shared experience.

You could plan your own unconference using these resources — with tips on logistics, funding, session formats, and more.

- How to organize an unconference (overview)

- How to Run an Un-Conference (role responsibilities)

- How to Run an Unconference (format and logistics)

- Unconference.net blog (tips for conference organizers)

- Introducing the Unconference Day (tips for primary facilitators)

- How to run a great unconference session (tips for participants)

Consider partnering with an academic department, such as those in the human services or STEM fields, to host an unconference. Professionals in these fields are often tackling tough problems whose solutions contribute to the common good.

Pitch to departments how an unconference is perfectly structured to help participants explore the complex problems within the department’s field. An unconference may even spark some ideas for undergraduate research projects.

Or, you can show the department this example of an unconference that was geared towards academics and professionals in the field but was managed by undergraduate volunteers.

Liberating Structures

The premise of Liberating Structures, as developed by Keith McCandless and Henri Lipmanowicz is that organizations achieve more when everyone feels included and engaged.

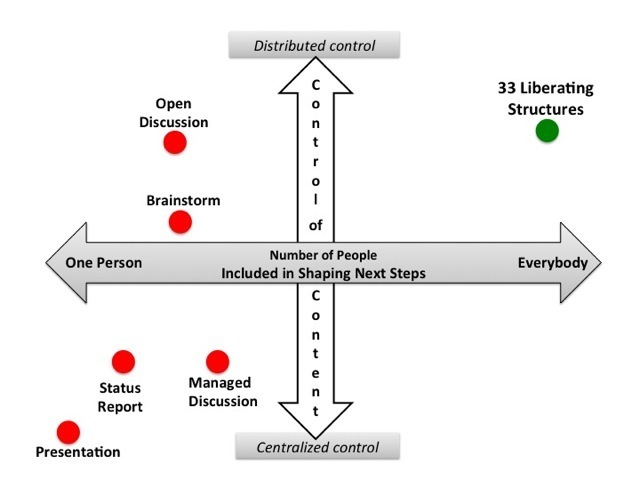

Liberating Structures is both a set of activities and a mindset. This mindset rests on the idea that members’ potential within an organization is limited when the microstructures that govern their relationships and routines are used to concentrate power around a handful of individuals.

A Liberating Structures mindset has people identify those microstructures so that they can be replaced with more inclusive activities. The most common microstructures that are used in organizations are presentations, open discussions, managed discussions, status reports, and brainstorming sessions.

Workshop with students on how they can use the 33 Liberating Structures activities to democratize their meetings. Have students identify the microstructures that they use most often and use this worksheet to substitute a Liberating Structure instead.

The success of Liberating Structures lies in how it makes tiny shifts to the ways in which we meet, plan, decide, and relate to each other. These shifts are made by tweaking the five design elements that underlie all microstructures:

- The structure of the invitation (participants being invited to collaboratively decide priorities sets a better tone than an agenda arbitrarily set by the facilitator)

- How the space is arranged and what materials are needed (a meeting with chairs arranged in a circle will often have better outcomes than a meeting arranged like a lecture)

- How participation is distributed (everyone should be given equal time during discussions instead of prioritizing the voices of senior-ranking members)

- How groups are configured (utilizing breakout groups breaks up monotony during meetings)

- The sequence of steps and time allocation (building in time for silent reflection or pair-and-shares reduces the amount of time focused on the facilitator)

As you decide how to approach the topic of power dynamics with students, you should aim for students to reflect on these issues long after the program is over. Students should want to actively strive to identify the equity issues around them and initiate the change that they want to see in their communities.

What questions do you still have about power dynamics and leadership structures? Connect with us on Twitter @themoderncampus and @JustinTerlisner.