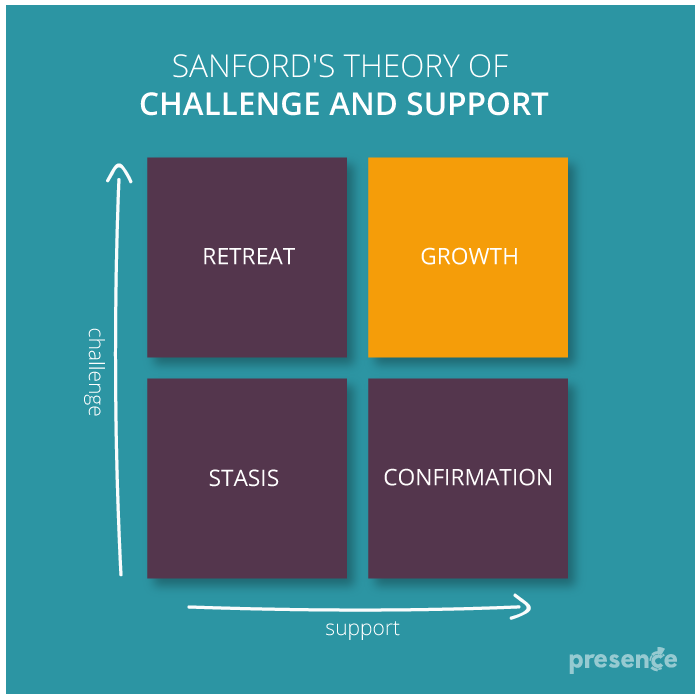

Readiness + Challenge + Support = Success.

We’ve known there exists an optimal balance to obtain the result of the above equation since Nevitt Sanford first proposed his theory in the 1960s.

Although this theory is primarily applied to students, I often see individuals struggle (and sometimes fail) to complete a task or project when there are people, areas, or resources that could offer support. I also see areas willing to help and support activity across campus, but that are not utilized.

But why?

While it seems we must be missing something if people struggle with a task and do not utilize available resources, there can be a number of reasons why this might occur.

One reason could be the Dunning-Kruger effect, which describes people’s ability to believe they are more competent than they truly are. This is typically the result of ignorance and not ego; people may not know what proficiency in a given area looks like or may not receive appropriate constructive feedback from others or their environment.

Another reason why this occurs is that people might be trying to demonstrate their abilities.

This could be to impress their boss, colleagues, or even just to prove perseverance to themselves. While such an approach could yield task completion, it may still be frowned upon due to lack of efficiency, lack of collaboration, or ineffective use of available resources and supports.

To that point, the reason people might not utilize other resources could be they are not aware of other people or resources aligned with their efforts or serving in a capacity to offer assistance.

This is not a rare situation.

Where institutional alignment of strategy and operations does not exist or is not clearly and regularly communicated, it’s easy to lose sight of what other areas are doing or how their work may align with your own. Additionally, people can be improperly onboarded to their area or institution and simply unaware other areas, people, or services exist.

Without naming names, I’ve encountered multiple institutions whose staff are not even aware of policies, practices, resources, or even upper-level people within their own teams. When this exists, it’s no surprise that ignorance of other resources across campus could persist.

What supervisors can do

Set clear expectations

Institutions can be more transparent about institutional connections, the expectation of collaboration, and general performance standards. While colleagues certainly appreciate a task simply being completed, supervisors can assist their direct reports in emphasizing what success can look like or pointing to an employee who excelled at being a team player, collaborating, or working efficiently and effectively.

Provide constructive feedback

To combat the Dunning-Kruger effect, supervisors can make constructive feedback the norm in all settings. Instead of just showing or telling someone they were wrong, take the time to explain the discrepancy between their behavior and what was expected. Do not assume comprehension; communicate to share examples as needed to reach a common understanding. Such behavior helps limit ignorance and gives people an opportunity to improve based on what competency or proficiency truly looks like.

Make time for development

Beyond talking tasks, make time to talk to your supervisees about their experience. Challenge them on ways in which they could grow, reflecting on their performance. Seek to understand their interests and intended development, then offer assistance by means of challenge or support, as appropriate. As Sanford’s theory implies, be careful to strike a balance in not overwhelming them with too much challenge, as well as not flooding them with support. The more you know about your supervisees, the better you’ll be able to balance this give and take. It’s also important to let them know you care and are willing to discuss their development outside performance evaluations.

What supervisees can do

Be transparent about your needs

Self-awareness is part of Sanford’s readiness aspect, one cannot best engage in challenge and support without this information. To aid your personal work, be open with your supervisor about how you operate and your goals. Let them know how you are feeling, whether you are ready and willing to take on more responsibility, and in what areas you are feeling uneasy or could utilize assistance. Sharing your work style, strengths, desired areas to improve, and goals provides an element of self-authorship for you, while also informing (and ultimately helping) your supervisor work with you.

Do your homework

Know what’s expected of you in your role. For areas where you do not have as much experience or for unfamiliar assignments, seek out examples. Know what expertise exist inside your institution and outside through your professional network or other resources. Engage with your colleagues and supervisor about strategies to seek support, as well as opportunities to feed challenge-seeking interests.

Build institutional connections

Despite how unique we believe our jobs and tasks are, you would be hard-pressed to identify tasks truly and squarely a sole responsibility with no impact, interest, or relationship to another entity on campus. Consequently, there are a number of advantages to meeting other people on campus, including byproduct benefits for the benefit of multiple parties. With that in mind, it doesn’t hurt to increase your network both to call for support or to undertake and accept a new challenge.

Everyone can ask for help

These principles apply to everyone. At some point, everyone benefits from assistance. Even if you accomplished something on your own, your performance could have potentially been enhanced if the right resources or assistance was sought ahead of time. Do not let your pride, apprehension, or anxiety prevent you from making a very normal and natural request for help.

Supervisors should role model this for their teams. They can do so by showcasing when asking for help from another person or area. They can also demonstrate this by personally asking members of their own team to offer assistance, pointing out the instance of seeking the support as opposed to just delegating a task or assigning a project.

In addition to supporting their supervisors, supervisees can model this for their colleagues when faced with a situation requiring assistance. A good colleague could also keep their eyes and ears open for instances where someone might benefit from help or assistance from another. Make yourself a connector or offer assistance yourself, where and when appropriate.

Complementing the information above, everyone could try the following to become more aware of institutional areas, resources, and potential support available:

- Review institutional strategic plans for alignment to other areas and initiatives

- Review institutional organizational charts to identify who might be appropriate to engage

- Look at the institution’s website content to learn more about a given area

- Email and cold-call folks to learn more about an area and how you could align efforts

- Set-up meet-and-greets with people across campus to establish more institutional connections

While not all of the information covered here applies to everyone, some of these suggestions are good practices to put in place or promote anyway. Awareness of resources, alignment of initiatives, willingness to collaborate, and knowing more people across campus can have beneficial byproducts. As an assessment professional – leading by influence due to lack of authority – these kind of actions are key to how I operate and promote with others. I can assure you, the more these pieces are in place, the better for everyone.

Supervisors and supervisees alike can benefit from revisiting Sanford’s theory of readiness, challenge, and support. This can be beneficial for self-reflection on conducting oneself and maintaining your own balance, while also being the best colleague to others at your institution.

It’s a reminder of our investment in ourselves and others can take many forms by way of challenge or support depending on what they need or request.

Now, here’s another ask: How have you asked for help at work? Let us know @themoderncampus.